“If I look at the mass I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.” – Mother Theresa

The Identifiable Victim Effect

On October 14, 1987, 18 month-old Jessica McClure fell into a well in Midland, TX. After 58 hours, rescuers were finally able to pull her out of the well. In that time, her situation had become a media sensation and Jessica received more that $700,000 from donors across the United States. Why did donors feel so compelled to make a donation directly to this child instead of organizations that serve to rescue much larger populations of children in danger? This pattern of giving, known as “The Identifiable Victim Effect”, can be witnessed on a daily basis.

Peter Singer, author of “The Life You Can Save,”conducted an experiment to observe this behavior firsthand. The experiment involved three groups of participants who were each given monetary compensation for their participation. Each group of participants were presented with the opportunity to donate a portion of their compensation to an organization whose mission it was to help feed Malawian children in need.

- The first group received information about the charity and about the hunger crisis in Malawi with the statistic that 1 million children were affected.

- The second group was shown a photo of a young Malawian girl named Rokia. They were told that she was very poor and that their donations could greatly improve her life.

- The third group was given the photo of Rokia as well as information about the charity (a combined, less detailed version, of the stories from the first two groups).

The second group gave almost twice the amount of donations that the first group gave. The third group gave slightly more than the second group.

Another study sought to measure the rate of “Compassion Fade” (a measure of the rate of decrease in action) as it related to the number of victims (1, 2, or 8). The results concluded that there was a much higher rate of “Compassion Fade” between the 1-2 victim condition than with the 2-8 victim condition. (Vastfjall, Slovic, Mayorga, Peters 2014) In other words, while the number of people in a group do matter, the distinction between an individual and a group (no matter what the size) was a key determinate in the levels of compassion shown towards the issue.

Sea Monkeys as a Model for Compassionate Behavior

Why are we more inclined to show compassion towards individuals as opposed to groups?

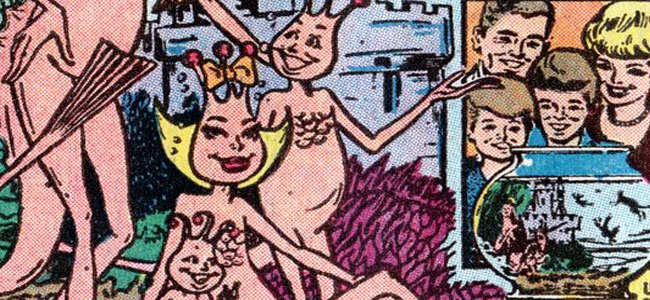

Carey Morewedge, a professor out of Boston University who studies the psychology of decision making, conducted a study along with his colleague J. Schooler to answer this very question. The inspiration for this study began when he purchased sea monkeys for his young daughter. The population of pet sea monkeys slowly dwindled from a few dozen to one, lone sea monkey. He noticed that his children became increasingly attached to this one sea monkey. Their concern for its wellbeing was in drastic contrast to the attitude that was attributed to the large mass of sea monkeys that had previously existed.

In the study, participants were shown an image that depicted 1, 2, 3, or 4 sea creatures. As the participants observed the selected image, the researchers measured their reactions to questions that concerned the possession of beliefs, desires, consciousness, and intelligence of the creatures. There was a direct correlation between the number of creatures present and the likelihood that participants would associate them with high-level mental states. The fewer creatures present, the higher the association. (Morewedge and Schooler, 2009)

The responses observed in this study fit into the larger idea that people have a strong connection to things which have tangible information vs. abstract information. What makes something tangible? The more detailed information we have about something, the more tangible that thing becomes. Likewise, the more “psychologically near” we are to something, the more tangible that becomes. “Psychologically near” is a a term used to describe how close the information is to our current state. For example, things that are occurring in the present are more “psychologically near” than things that occurred in the past. As individuals, we are more “psychologically near” an individual than a group. This nearness leads to a stronger connection to that individual as a result of the tangible information we have been able to process. That connection fosters a greater level of compassion.

How to Foster a Greater Sense of Compassion

- Focus on individuals – This kind of appeal will create a deeper and stronger connection with your audience. As the studies have shown, the individual story has a greater resonance with potential donors compared to details/statistics about a group of people.

- Give solid information – On a personal note, as a fundraising specialist, I’ve noticed that many campaigns leave out crucial details including budget breakdowns, project timelines, case studies/ success studies (if applicable). Not only does this type of information increase the tangibility of the issue at hand, it also helps foster a sense of trust in the organization.

- Show the impact of the funds given – There’s one last concept I’d like to introduce in this article: Futility Thinking. Studies have shown that people are less likely to make a donation as the relationship between the help rendered applies to a smaller and smaller portion of those in need of help. For example, people given the chance to save 1500 people in a refugee camp that included 3000 people were much more likely to make a donation in comparison to people who were given a chance to save 1500 people in a refugee camp of 10,000 individuals. At some point, a person’s donation can feel like a drop in the ocean and the donor is left wondering what difference their one gift could make. In order to maintain a sense of significance for every donation received, some nonprofits have begun framing their campaigns in terms of each dollar’s impact. For instance, an educational organization may tell you that for every $50 received, a student receives the essential educational material for that semester.

Sources: The Critical Link Between Tangibility and Generosity, Too Many to Care, Why Donors Don’t Give, Compassion Fade: Affect and Charity Are Greatest for a Single Child in Need, Statistical, Identifiable and Iconic Victims and Perpetrators